Welcome to Dr. Nelson's

Osteoarthritis Page

First posted June 8, 2000 Last updated February 13, 2012

A newer page on osteoarthritis is posted elsewhere on my site. Click the link.

|

Patient with osteoarthritis of the hand. |

|

|

Patient with osteoarthritis of the hand, clinical photo on left, same patient's xrays on right. |

|

![]()

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is inflammation (redness, swelling, and pain) of the joints. It is very treatable, and that is the most important thing to remember as you read this site. Osteoarthritis is rarely deforming or crippling, although it can be painful if not treated. The deforming and crippling arthritis is rheumatoid arthritis, which is a very different disease. Osteoarthritis

is very common and affects almost everybody as they get older. The older

you get, the more likely you are to have it, and around eight out of

ten people over the age of 50 are affected. |

|

More severe osteoarthritis

Whenever the joint space is narrow, it means the cartilage on that joint is worn away (like bald tires imply that the tread is worn away). |

|

Osteoarthritis can be thought of as "wear and tear" arthritis. It is not the same as rheumatoid arthritis, which is an autoimmune disease in which your body thinks that you are allergic to your joints. Rheumatoid arthritis is very deforming and can be crippling. Osteoarthritis does not deform the hands in the way that rheumatoid arthritis does .

![]()

If you want to see more xrays of arthritis, read this section. If you want to move on to what osteoarthritis is, skip to the next section.

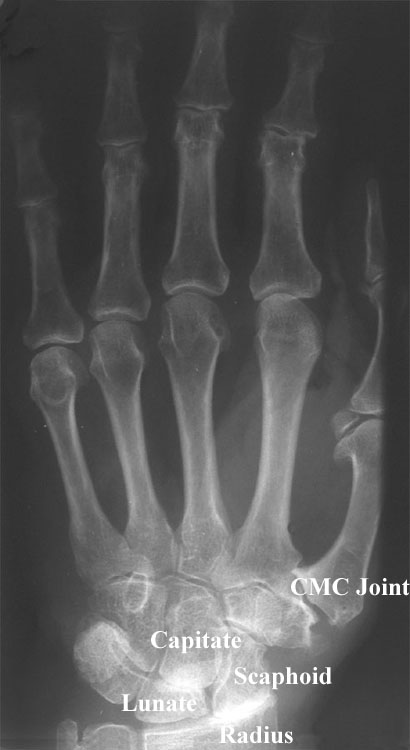

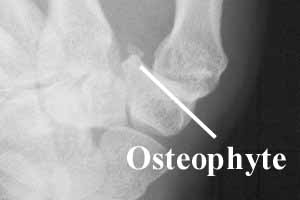

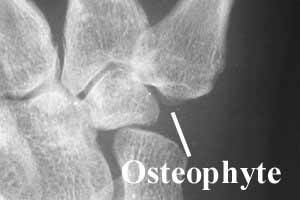

This is a patient has advanced arthritis. The joint space between the scaphoid and the radius is narrowed down to bone-on-bone contact. The capitate-lunate joint space is also zero. The bone below the cartilage (called the "subchondral bone") is white and hard. There are many areas of small bone growth at the edges of the bone, called "osteophytes." This complex of problems is called Scapho-Lunate Advanced Collapse, or SLAC wrist. In addition, the CMC joint of the thumb shows changes in the shape of the bone and the bone of the thumb has moved over to the right, which is called "lateral subluxation."

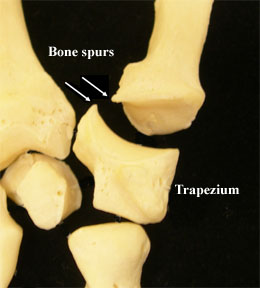

This is a photograph of the bones of the wrist, at the same location as the above xray. Note the bone spurs (little edges of bone) sticking out from the CMC joint.

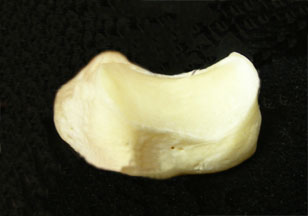

This is close-up view of one of the bones in the upper photograph, the trapezium. It is the wrist bone that the thumb rests on. Note the ridge of bone extending all the way around the upper joint in the photograph. This is the "osteophyte" or "bone spur" that we see in the xray. The osteophyte is not just a bump at one side of the bone, but extends all the way around the joint. We

![]()

What is osteoarthritis on a microscopic level?

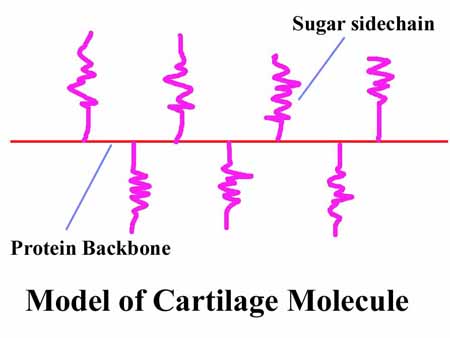

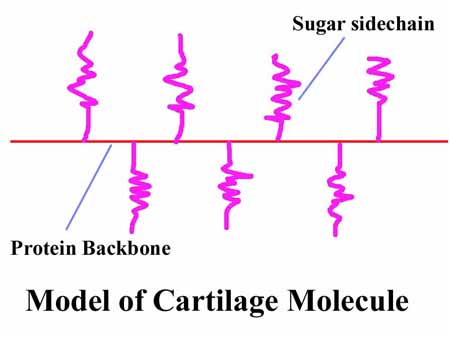

Osteoarthritis is wearing out of your cartilage. What is cartilage? It is the white, smooth, shiny material at the ends of your bones, it is the "ball bearings" that allows the joints to move smoothly. Your cartilage is made of a rather large and complex molecule. I have drawn a representation of it here:

The cartilage molecule is made up of hundreds of sugar sidechain molecules attached to a protein molecule backbone. The sugar molecules love to associate with water, so there is a lot of water in cartilage. As you use a joint and place pressure on the cartilage, the water tends to squeeze out, which both makes your joints auto-lubricating and makes the cartilage bouncy, like a wet sponge. This helps to decrease the load on your joints as you move.

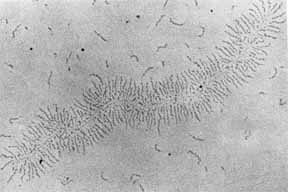

Scientists have made electronphotographs of the cartilage molecule, and it looks like this. Note the sugar sidechains and the protein backbone:

|

Actual electron photomicrograph of a cartilage molecule (proteoglycan).

Note the protein backbone and the sugar sidechains sticking out to the side.

In summary, your cartilage is based on a large, complex organic molecule, with a protein backbone and sugar sidechains, as shown above. In addition, it has cells and other components, as shown below.

|

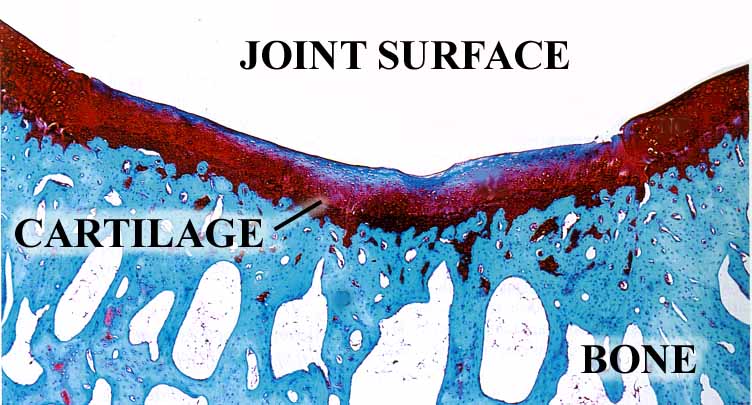

In this photomicrograph, the joint surface is at the top and the bone is at the bottom. The round things are cartilage cells, and they produce the cartilage molecules. (Cartilage photomicrographs are some of the most beautiful of all histology slides!)

Osteoarthritis starts with biochemical changes in your cartilage. The sugar sidechains like water, and cartilage is a bit like a wet sponge. The water molecules squish out as we walk or press on our joints (with the water acting a bit like a lubricant), and seep back in when we take force off our cartilage. With age, we tend to lose some of the sugar sidechains, which changes the biomechanical characteristics of our cartilage (the sponge becomes less wet and therefore less resiliant). It becomes stiffer and loses some of its self-lubricating ability. The result is that the cartilage starts to wear, becoming thin. The surface becomes rough; it is no longer a smooth bearing surface.

The photographs below show the changes in your cartilage as the sugar sidechains are lost. The photomicrograph on the left shows normal cartilage. The red material is the cartilage, the blue material (with holes like Swiss cheese) is the bone supporting the cartilage. On the right, you can see a roughening of the joint surface, with tears in the surface and pieces of cartilage breaking off in strands. There is also a crack in the cartilage, extending down into the bone. Over time, the cartilage can wear out completely, with bare bone in the joints.

|

|

|

Photomicrograph of normal cartilage

|

Photomicrograph of arthritic cartilage

|

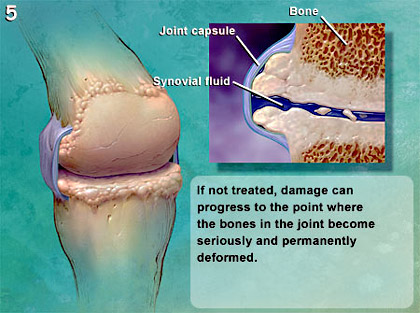

At the same time, many other changes are occuring. The joint capsule becomes thicker and more synovial (lubricating) fluid is manufactured which makes the joint swell. In addition to cartilage degeneration, the bone along the edge of the joint responds to the changing biochemical and biomechanical environment, growing bony ridges called osteophytes.

![]()

What does this mean in my joints?

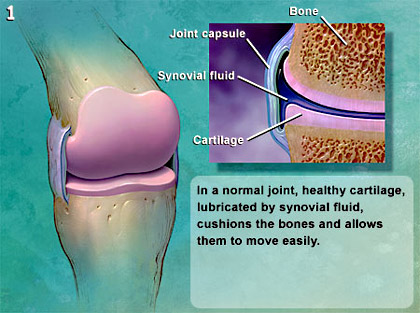

At the earliest stages of osteoarthritis,

your joints look like this:  |

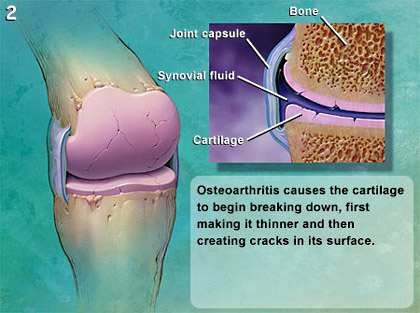

As your osteoarthritis progresses, it looks like this:  |

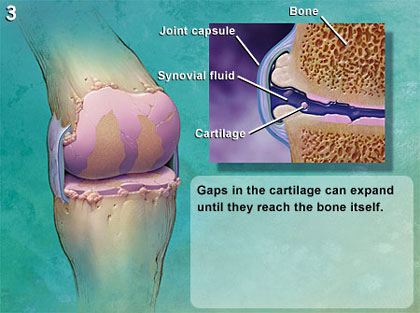

Advancing osteoarthritis looks like this:  |

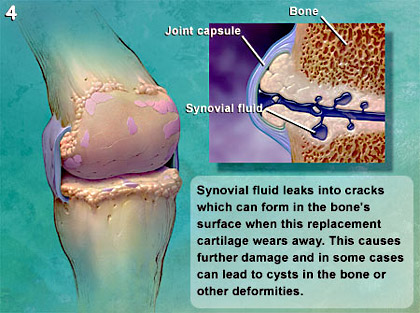

Patients with this level of osteoarthritis usually have pain most of the time:  |

This is the end stage of disease. Note that there is no cartilage left on the end of the bone:  |

This series of images is from

MedcoHealth |

![]()

What are the symptoms of osteoarthritis?

The hallmarks of osteoarthritis are joint stiffness, swelling, and pain. This often improves with light activity, but is usually worse again after forceful gripping or pinching, or after a period of rest.

![]()

Who gets osteoarthritis?

Many people think osteoarthritis should come from a long history of hard work, but hard labor does not seem to be very related. Osteoarthritis can be due to trauma such as an old fracture, but it is usually just due to the effects of aging coupled with some hereditary contribution.

![]()

How is osteoarthritis diagnosed?

The diagnosis is made by listening to the patient and by examining the patient. Most patients will have a history of slowing increasing pain, stiffness, and swelling over a period of years. Sometimes there is a farily sudden onset of symptoms, usually associated with a single episode of trauma (typically a fall) or a period of overuse (weeding the garden, say, or packing to move). An xray examination confirms the diagnosis. Often there will be no correlation between the amount of pain and the severity of the arthritis as shown by the xray.

![]()

What does the xray show?

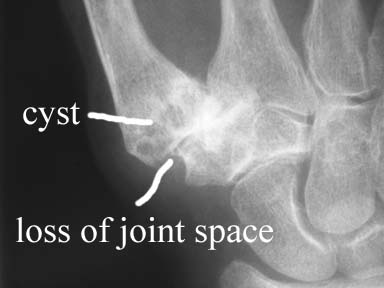

The xray typically shows some joint space narrowing, that is, the white shape of the bones are closer together than they normally are (see the xray above). The bone along the joint is usually whiter (called "sclerosis") and may have little points of bone growing out (called "osteophytes"). There may be holes in the bone ( called "cysts") and the bones may be starting to slide out of alignment (called "subluxation"). I will review your xrays with you and explain exactly what I see.

|

|

|

![]()

This patient has more advanced osteoarthritis. Note the complete loss of joint space (no space between the bones of the thumb), cysts (holes in the bone, shown as the small black areas in the base of the thumb metacarpal, which is the large bone on the upper left side of each view), large osteophytes, and some lateral subluxation (the thumb metacarpal has slid off to the left of the bone it touches, the carpal bone called the trapezium). (more on the names of the bones here)

This patient has even more advanced osteoarthritis. Note the complete loss of joint space, the large osteophytes, the loss of the size of the trapezium, and the fact that the thumb metacarpal (the bone on the left in each image) has started to collapse toward the palm (see on the left image).

![]()

How is osteoarthritis treated?

|

Patient Education

I believe that the key part of treating osteoarthritis is patient education, which is why I created this website and wrote this paper. Once the patient understands what is going on, they can take charge of managing their condition. Osteoarthritis cannot be made to go away; getting younger is the only thing that will do that (we are working on it!). Osteoarthritis is not "cured", but managed. Patient involvement in that management is key.

Activity Modification

The next step after patient education is activity modification. Learn what activities exacerbate your pain, and see if you can avoid them. For instance, opening tight jar lids puts a great strain on your thumb base joint. Get a plastic sheet from me when you see me, or ask someone else to open jars. If you have faucets that are leaky or stiff, replace the gasket or grease the threads. Look at the activies throughout your day and identify which ones cause you pain. There are many different kinds of pens around that allow you to write without upsetting your thumb base. Check out this link, it is a page I have written and illustrated showing you the many options available to avoid pain when writing.

Along with activity modification, there are a number of patient-directed therapies which can help. Pain can be relieved by applying heat to stiff and painful joints for 20 minutes up to three times a day. Various deep heat lotions, heating pads, infrared lamps, hot baths etc. can be used. Swimming in a heated pool can help.

Medication

The first medication that you should try is acetamenophen (Tylenol is the best-known brand of acetamenophen). The maximum amount you can take per day according to the FDA is 4000 mg. It will not upset your stomach the way that Motrin or aspirin do, and will help to offset the pain of minor arthritis. Most patients have tried this long before they have seen their doctor, and still need something more, so I will not dwell on this. Just remember: start with acetamenophen.

The next class of medications that should be tried are called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAID's. These drugs block the enzyme (cyclo-oxygenase) that creates the pain. For more information, see my essay on anti-inflammatory medication and COX-2 inhibitors. Motrin is the most common NSAID. The FDA has an upper limit of 3200 mg per day of Motrin. You should continue taking Tylenol with the Motrin, as the two drugs work better together than separately. This is called "synergy", and a simple way of expressing this is " 1 + 1 = 3".

There is some increased risk of heart attacks and strokes with all NSAID's. See the FDA's guide for patients to NSAID's.

If you have a history of stomach ulcers, COX-2 inhibitiors such as Celebrex, may be better for you than simple NSAID's.

The medical management of arthritis is complex and you should read all of these pages and discuss with me what is right for you.

Steroid Injections

Steroid injections can be very helpful to calm down a very painful joint. These are not the systemic steroids that cause road rage, osteonecrosis, and all the other bad things you have heard about steroids. These are highly localized treatments of steroids, which are a class of substances that your own body makes to calm down unwanted or excessive inflammation. I am allegic to pain, and presume that you are, too. I have learned a technique that is virtually painless, and almost every patient tells me that the shots that I give are the best that they have every had. I mean it.

Surgery

Surgery is reserved for last. It is only for patients whose osteoarthritis is so bad that they cannot manage their disease with activity modification, anti-inflammatory medication, and steroid injections. Indications for surgery generally involve patients who are so miserable with their arthritis that they cannot do the things in life that they want to do. Life is too short to give up all the things you like to do. If you have tried all of the above steps, and still have more pain and more limitations than you want to live with, talk to me about surgery. Some procedures are fairly simple and some are more complex. I can outline all of your options when you come in.

The treatment options for each joint are different. The most common arthritis, at the base of the thumb, is treated by cutting off the last 3 mm of the metacarpal and the first 3 mm of the trapezium, then placing a tendon into the space, to act as a "rubber baby buggy bumper", preventing the bone ends from hitting each other, and thereby resolving the pain. The distal interphalangeal joint (DIP, the one next to the nail) of the fingers or the interphalangeal joint (IP joint, next to the nail) of the thumb, is fused. An clinical example is here.

![]()

Additional Resources

Osteoarthritis is common, and many physicians agree with me that patient education is key to empowering the patient to manage their own disease. Therefore there is a lot of additional information available for you. You can select from:

American Society for Surgery of the Hand: Patient Education Brochure: Arthritis of the Base of the Thumb.

Here is some additional information that I have written:

Celebrex and Vioxx, the COX-2 Inhibitors

Chondroitin and Glucosamine

![]()

|

|

Here are some links you may want to examine. These are commercial sites, I have reviewed part of them (last time reviewed: June 4, 2000) and they seemed to be OK, but I am less sure of the accuracy of these sites than I am of the above sites. Let me know what you think of these.

General Arthritis Information:

Johnson & Johnson arthritis site called All About Arthritis

![]()

|

Would you like to search the medical library of the

National Library Medicine for scientific papers on this topic? Just

click on

|

Remember the admonition from the Patient Education Links Page: the Internet has a lot of information, much of it incorrect. I have reviewed the sites that I have linked to, and have only linked to sites when I personally know the surgeon who posted it, or am a member of the organization that posted it. However, I may not agree with all that is on that site, and it may have changed since I reviewed it. If any of the information is not consistent with what I have told you, please download the material and bring it in.

|

return to |