Acorn woodpecker with eponymous seed (from Internet)

The Acorn Woodpecker is a familiar sight at the Ranch, as well as a familiar sound. Highly social, they live year-round in cohesive social units. These birds breed communally, with several fertile females laying eggs in a nest cavity. DNA studies have shown that there are multiple fathers represented in the nest. The females try to destroy the eggs of the other at the beginning of nesting season but finally stop the killing and concentrate on laying eggs. The young are fed by related adult and subadult females.

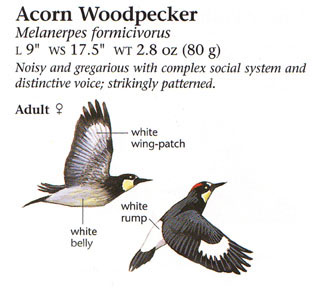

Image from Sibley's Guide to Birds

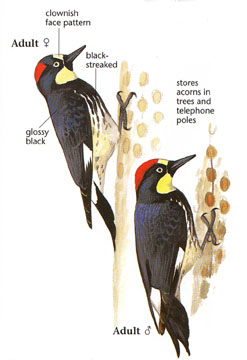

Image from Sibley's Guide to Birds

The birds store acorns communally in trees called granary trees. The communal nature of this is not entirely clear, but it is thought that a group of birds can more successfully defend their hoard of food against robbers such as jays or flickers. One of our most notable granary trees is at the end of Prune Ridge.

The Granary Tree at the end of Prune Ridge, just before you drop to the Hook, in April 2008 is quite bare.

The Granary Tree in November of 2006 is quite full of acorns.

The birds store the acorns for the nuts, not for any insect in them.

The textures of the trees and the nuts is very interesting.

The Acorn Woodpecker is widely distributed. It is found from northwestern Oregon, California, the American Southwest, and western Mexico through the Central American highlands and into the northern Andes of Colombia. They can be found anywhere oaks are plentiful and less commonly can be found where there are widely dispersed oaks but with other suitable habitat. They are hightly territorial, protecting the best foraging areas.

The diet of the Acorn Woodpecker is seasonally determined. The main diet of the Acorn Woodpecker in spring and summer consists of insects, but they also eat sap, oak catkins, fruit, and flower nectar; and occasionally grass seeds, lizards and bird eggs. The bird prefers, however, flying ants and other Hymenoptera (ants and bees) and Coleoptera (beetles). When catching bugs on the wing, called "flycatching", the woodpecker sits at the tops of trees or on branches that extend out from the forest, giving them a better view of the insects. Most foraging, however, is performed in or near the canopy. I have seen them swoop out and catch flying insects on North Flat, just like the Black Phoebe. The woodpecker rarely goes to the ground except to pick up grit and fallen acorns. I have seen them on the upper reaches of Matteoni Ridge, on bare gravel areas. I could not see what they were eating, but it could be grit, seeds or insects. It was definitely not acorns, although they were in season.

At Hastings Natural History Reservation in central coastal California, flycatching is "undoubtedly the major foraging method of these birds throughout April and May, only to be replaced in importance by sapsucking in June and July." Sapsucking is a communal affair and group members congregate at a set of holes that are used repeatedly for several years.

Their diet changes as insects are less common, the sap flows less, and the acorn crop ripens. Usually, acorns are removed singly from trees, but the bird may also break off a twig holding up to three acorns. Acorns are critical for winter survival. Storing in granaries is a community affair. It is thought that the social nature of Acorn Woodpeckers relates to the storing of such large quantities of acorns and the effort it takes to guard the granaries from theft by jays, flickers, and other birds and animals. Failure of one species of oak to produce fruit is usually compensated for by the success of other species. The black oak is a favorite food, based on my examination of the granary at the end of Prune Ridge, but acorns of other species of oak are recorded in the literature as food items.

They drink water daily and will cross the territory of other flocks to get to water. They are commonly seen at the tubs near the cabin.

The breeding season in our area is from April to June, with the majority of nests begun between April 15th and May 15th. They have one of the most bizarre mating systems of any bird in the world. They are COOPERATIVE BREEDERS and live in groups composed of up to 6 COBREEDER MALES, 3 JOINT-NESTING FEMALES, and NONBREEDING HELPERS of both sexes. COBREEDER MALES are brothers and/or fathers and their sons competing for matings with the JOINT-NESTING FEMALES, who are sisters or a mother and her daughter who lay their eggs in the same nest cavity. Offspring produced from this communal nest may remain in their natal group for several years as NONBREEDING HELPERS, during which time they help feed younger siblings at subsequent nests.This kind of mating system is known as POLYGYNANDRY. All individuals within the group are close relatives except that cobreeder males are not related to joint-nesting females. INCEST AVOIDANCE is maintained because helpers only inherit and become cobreeders following REPRODUCTIVE VACANCIES when the breeders of the OPPOSITE sex die and are replaced by unrelated birds from elsewhere. Reproductive vacancies are often filled by a unisexual set of siblings who compete against other sibling groups in spectacular events called POWER STRUGGLES. Winners of power struggles become cobreeders in the new group; losers return home and resume nonbreeding helper status.

|

There is also a great deal of competition for reproduction within groups. Joint-nesting females even destroy each other's eggs, removing them from the nest during egg-laying and placing them in a tree where group members come and eat them. Since joint-nesting females are close relatives, birds are destroying eggs that are also related to themselves!

At left is a female (head with white, black and then red) removing her sister's egg. You can tell she's a female because of the black band on her forehead; adult males and juveniles have solid red foreheads. (from Hastings Reserve, cited below) |

According to a study published online in 2002 by Walter Koenig, who has made a career out of studying Acorn Woodpeckers, joint-nesting females share reproduction more equitably than expected, apparently because egg destruction and the inability of females to defend their eggs from cobreeders eliminate any possibility for one female to control reproduction. For males, however, reproductive skew is high, with the most successful male siring over three times as many young as the next most successful male.

The bird uses its tail to support its movements up and down the tree (see photo, below). The feathers are special, much stiffer at the tip than a normal feather. I have one in my Ranch Journal, it is quite different from a normal feather.

Sources

http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Melanerpes_formicivorus.html (8/12/09)

http://www.prbo.org/calpif/htmldocs/species/oak/acwoacct.html (8/12/09)

http://www.hastingsreserve.org/Resident%20Web%20Pages/Koenig%20Web%20Pages/AWIntroPoster/AWposter.html(8/12/09; breeding information)

http://www.pnas.org/content/99/10/7178.full (text of Koenig's reproductive skew paper)

Photo of bird perched, leaning on stiff feathers, is from Bay Nature Flicker site.

For a 437 page book on Acorn Woodpeckers by Walter Koenig, see Google at http://books.google.com/books/princeton?id=zmgiuAdhTd8C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=&f=false